一.go语言介绍

1.Go语言简介

2.Go语言创始人

对语言进行评估时,明白设计者的动机以及语言要解决的问题很重要。Go 语言出自 Ken Thompson 和 Rob Pike、Robert Griesemer 之手,他们都是计算机科学领域的重量级人物。

贝尔实验室 Unix 团队成员,C 语言、Unix 和 Plan 9 的创始人之一,在 20 世纪 70 年代,设计并实现了最初的 UNIX 操作系统,仅从这一点说,他对计算机科学的贡献怎么强调都不过分。他还与 Rob Pike 合作设计了 UTF-8 编码方案。

2) Rob Pike

Go 语言项目总负责人,贝尔实验室 Unix 团队成员,除帮助设计 UTF-8 外,还帮助开发了分布式多用户操作系统 Plan 9,,Inferno 操作系统和 Limbo 编程语言,并与人合著了《The Unix Programming Environment》,对 UNIX 的设计理念做了正统的阐述。

就职于 Google,参与开发 Java HotSpot 虚拟机,对语言设计有深入的认识,并负责 Chrome 浏览器和 Node.js 使用的 Google V8 JavaScript 引擎的代码生成部分。

Go 语言的所有设计者都说,设计 Go 语言是因为 C++ 给他们带来了挫败感。在 Google I/O 2012 的 Go 设计小组见面会上,Rob Pike 是这样说的:

我们做了大量的 C++ 开发,厌烦了等待编译完成,尽管这是玩笑,但在很大程度上来说也是事实。

3.Go语言优势

- 语法简单

var a,b=1,2

a,b=b,a

fmt.Println(a,b)

- 可以直接编译成机器码

- 静态数据类型和编译语言

a:=1

b:=false

- 内置支持并发

go func() {

//do something

}()

- 内置垃圾回收

- 部署简单

- 强大的标准库

4.Go是编译型语言

Go 使用编译器来编译代码。编译器将源代码编译成二进制(或字节码)格式;在编译代码时,编译器检查错误、优化性能并输出可在不同平台上运行的二进制文件。要创建并运行 Go 程序,程序员必须执行如下步骤。

-

使用文本编辑器创建 Go 程序;

-

保存文件;

-

编译程序;

-

运行编译得到的可执行文件。

这不同于 Python、Ruby 和 JavaScript 等语言,它们不包含编译步骤。Go 自带了编译器,因此无须单独安装编译器。

5.为什么要学习Go语言

如果你要创建系统程序,或者基于网络的程序,Go 语言是很不错的选择。作为一种相对较新的语言,它是由经验丰富且受人尊敬的计算机科学家设计的,旨在应对创建大型并发网络程序面临的挑战。

在 Go 语言出现之前,开发者们总是面临非常艰难的抉择,究竟是使用执行速度快但是编译速度并不理想的语言(如:C++),还是使用编译速度较快但执行效率不佳的语言(如:.NET、Java),或者说开发难度较低但执行速度一般的动态语言呢?显然,Go 语言在这 3 个条件之间做到了最佳的平衡:快速编译,高效执行,易于开发。

Go 语言支持交叉编译,比如说你可以在运行 Linux 系统的计算机上开发可以在 Windows 上运行的应用程序。这是第一门完全支持 UTF-8 的编程语言,这不仅体现在它可以处理使用 UTF-8 编码的字符串,就连它的源码文件格式都是使用的 UTF-8 编码。Go 语言做到了真正的国际化!

6.Go语言适用场景

- 服务器编程.实现日志处理,虚拟机处理,文件处理等

- 分布式系统或数据库代理

- 网络编程,包含web应用

- 云平台

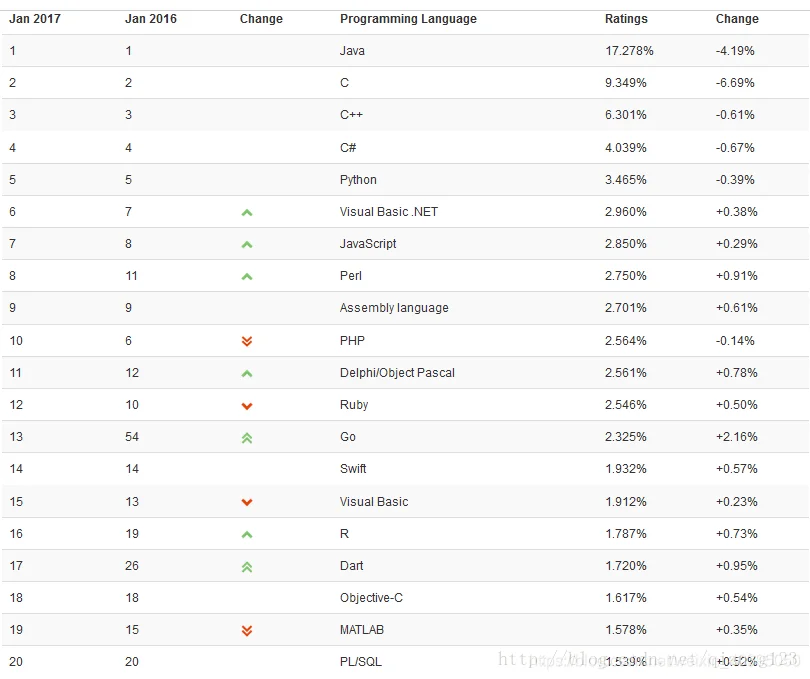

7.市场占有率

- 根据Tiobe中Go语言的排行在逐年上升.

8.Go语言吉祥物

二.环境变量配置

1.下载地址

- 由于Google退出中国,所以国内无法直接访问到Go语言的官网

- 但是可以通过Go语言中文网进行加载资源和交流Go语言技术

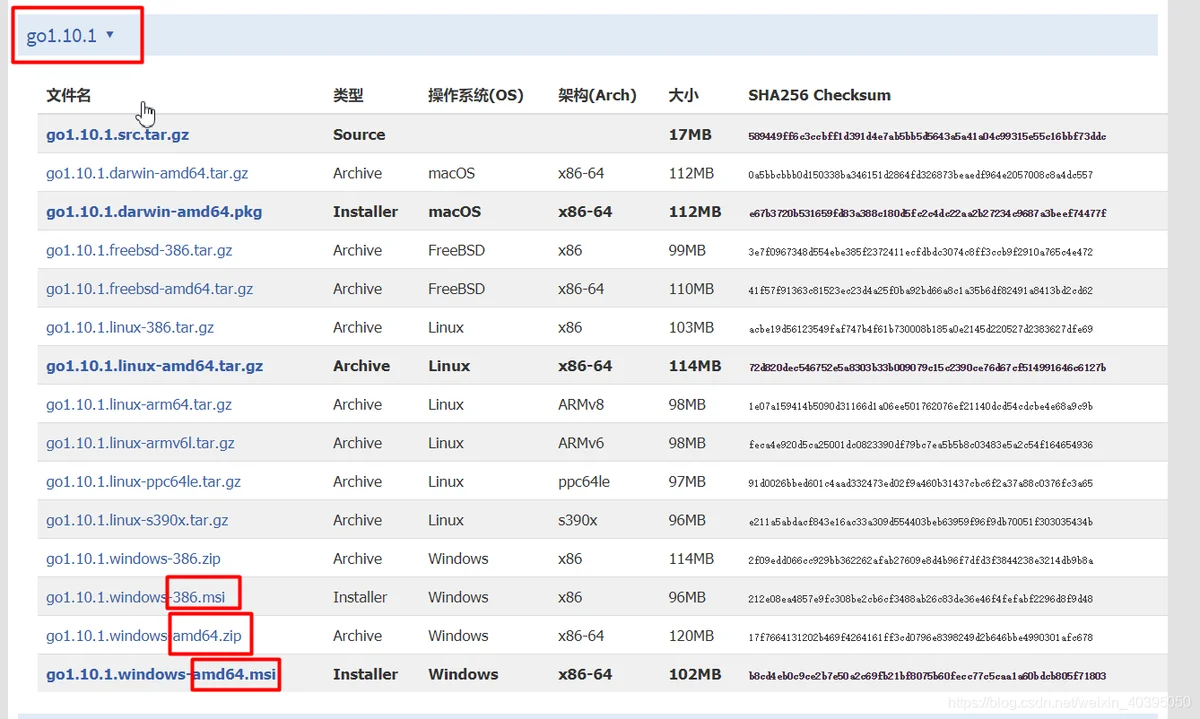

2.下载步骤

- 直接进入到Go语言中文网下载页面

- 选择要下载的版本

- 首先要确定版本号,本套视频使用的Go1.10.1

- 然后确定自己的操作系统,windows或linux等,本阶段使用Window操作系统进行讲解

- 如果是windows确定自己系统位数,32位系统选择386,64位系统选择amd64

- 扩展名.msi表示安装版.zip为解压版(推荐使用解压版,所有的配置都自己操作,心中有数)

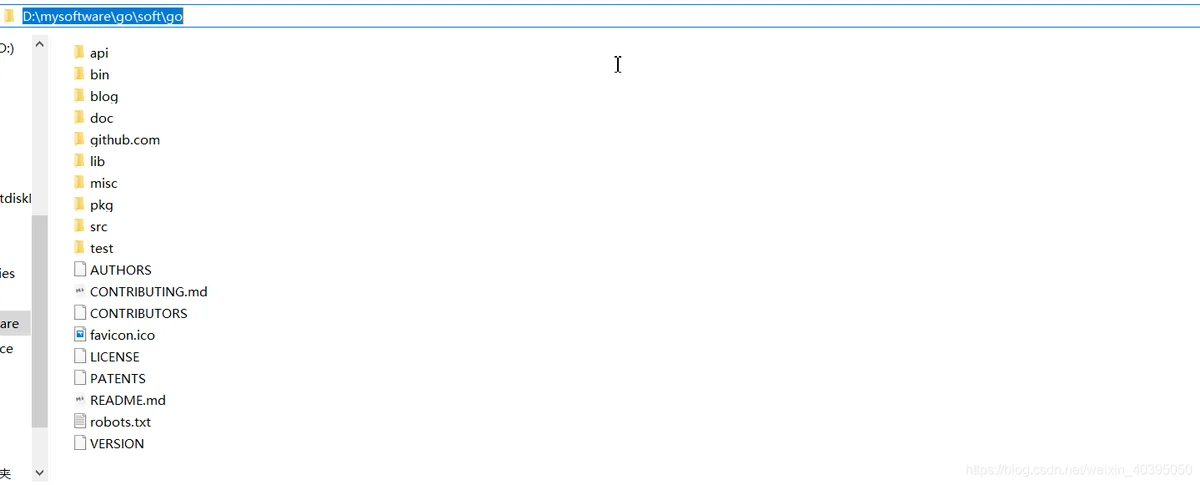

3.Go语言库文件夹解释

- api : 每个版本更新说明

- bin : 自带工具. 重点记忆

- blog:博客

- doc:文档

- misc: 代码配置

- lib:额外引用

- src:标准库源码,以后第三方库放入到这个文件夹中. 重点记忆

- test:测试

4.配置步骤(Windows举例)

- 把下载好的go1.10.1.windows-amd64进行解压,解压后出现go文件夹

- 把解压后的go文件夹复制到任意非中文目录中(例如: D:\mysoftware\go\soft\go)

- 如果没有配置环境变量默认去C:\go找Go语言库

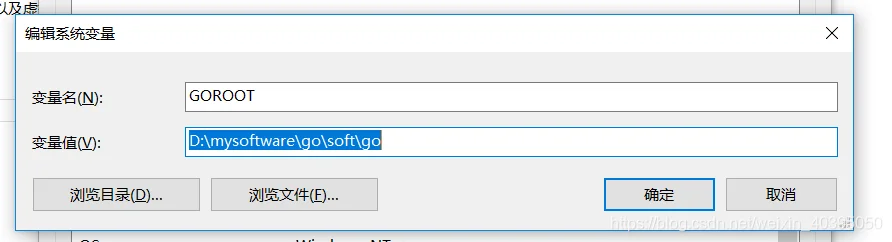

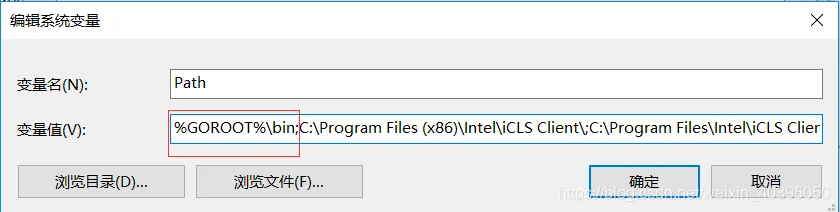

- 配置环境变量

- “我的电脑” --> 右键”属性”–> “高级” --> “环境变量” --> “系统变量”–> “新建”按钮后输入

%GOROOT%\bin;

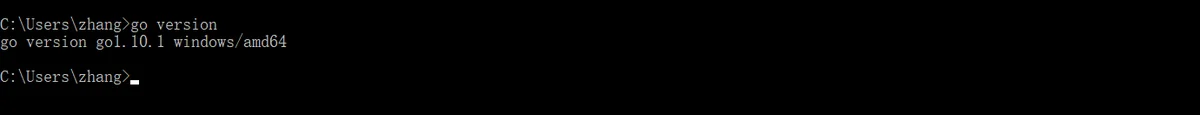

go versiongo env

5.环境变量参数解释

- GOROOT 表示Go语言库的根目录的完整路径

- PATH 中配置内容方便在命令行快速调用Go语言库中工具

- GOPATH 可以先不配置,在做项目时需要配置,表示项目路径

三.Hello World

1.编写前准备

- 在D:/盘下新建了一个文件夹,名称为go(这个文件夹名称任意,只要不是中文即可)

- 在go文件夹下新建了一个文件夹,名称为0103,代表着这是章节1的第3小节

- 为了能够在命令行中进行操作,需要先知道几个windows命令行命令

盘符名: #表示进入到某个磁盘

cd 文件夹名称 #表示进入到文件夹中

cd .. #表示向上跳一个文件夹

dir #当前文件夹中内容展示

rungo run XXX.go

2.Hello World编写过程

- 在D:/go/0103/新建记事本,并修改扩展名后名称为main.go

- 在文件中输入以下代码

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello World")

}

- 使用Windows命令行工具,输入以下命令运行观察结果

d:

cd go/0103

go run main.go

- 程序结果应该是输出

Hello World

四.Hello World编写过程注意事项

1.关于文件

.gomain.go.txt

main.txt

2.注释

- 注释是给程序员自己看的备注.防止忘记

- 编译器不会编译注释中内容.注释对程序运行无影响

- 注释支持单行注释和多行注释

//单行注释 ,从双斜杠开始到这行结束的内容都是注释内容

/*

多行注释

*/

3.package关键字

package main4.import关键字

import "fmt"//一个包一个包的导入

import "fmt"

import "os"

// 一次导入多个包(此方式为官方推荐的方式)

import (

"fmt"

"os"

)

- Go语言要求,导入包就必须使用,否则出现编译错误.例如导入了"fmt"和"os"包,如果只使用了"fmt"会出现一下错误信息

imported and not used: "os"

5.main函数

func main.\main.go:6:syntax error:unexpected semicolon or newline before {

fmt.Println()6.编码问题

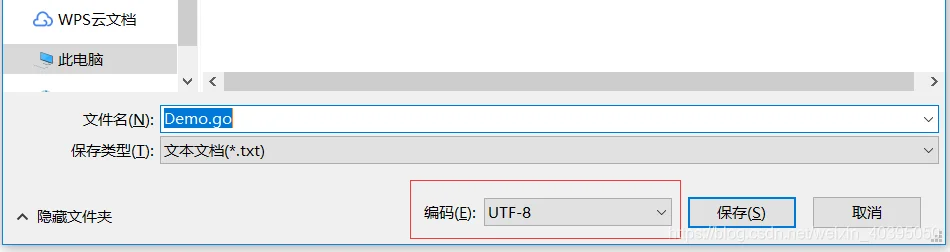

- Go语言适用UTF-8编码,编译整个文件

- 新建的记事本默认ANSI编码,所以要有中文需要把文件保存为UTF8编码

7.其他事项

- 整个文件中严格区分大小写

五.Go工具

1.解压版Go语言安装包中自带工具

- 在%GOROOT%/bin中有三个工具

- go.exe 编译、运行、构建等都可以使用这个命令

- godoc.exe 查看包或函数的源码

- gofmt.exe 格式化文件

--bin

--go.exe

--godoc.exe

--gofmt.exe

2.go.exe参数列表

go helpUsage:

go command [arguments]

The commands are:

build compile packages and dependencies

clean remove object files and cached files

doc show documentation for package or symbol

env print Go environment information

bug start a bug report

fix update packages to use new APIs

fmt gofmt (reformat) package sources

generate generate Go files by processing source

get download and install packages and dependencies

install compile and install packages and dependencies

list list packages

run compile and run Go program

test test packages

tool run specified go tool

version print Go version

vet report likely mistakes in packages

3.常用参数解释

go versiongo envgo listgo buildgo cleango vetgo getgo buggo testgo run六.godoc命令介绍

1.godoc 命令介绍

godoc [包] [函数名]2.godoc使用

- 查看包的源码

C:\Users\zhang>godoc fmt

use 'godoc cmd/fmt' for documentation on the fmt command

PACKAGE DOCUMENTATION

package fmt

import "fmt"

Package fmt implements formatted I/O with functions analogous to C's

printf and scanf. The format 'verbs' are derived from C's but are

simpler.

Printing

The verbs:

General:

%v the value in a default format

when printing structs, the plus flag (%+v) adds field names

%#v a Go-syntax representation of the value

%T a Go-syntax representation of the type of the value

%% a literal percent sign; consumes no value

Boolean:

%t the word true or false

Integer:

%b base 2

%c the character represented by the corresponding Unicode code point

%d base 10

%o base 8

%q a single-quoted character literal safely escaped with Go syntax.

%x base 16, with lower-case letters for a-f

%X base 16, with upper-case letters for A-F

%U Unicode format: U+1234; same as "U+%04X"

Floating-point and complex constituents:

%b decimalless scientific notation with exponent a power of two,

in the manner of strconv.FormatFloat with the 'b' format,

e.g. -123456p-78

%e scientific notation, e.g. -1.234456e+78

%E scientific notation, e.g. -1.234456E+78

%f decimal point but no exponent, e.g. 123.456

%F synonym for %f

%g %e for large exponents, %f otherwise. Precision is discussed below.

%G %E for large exponents, %F otherwise

String and slice of bytes (treated equivalently with these verbs):

%s the uninterpreted bytes of the string or slice

%q a double-quoted string safely escaped with Go syntax

%x base 16, lower-case, two characters per byte

%X base 16, upper-case, two characters per byte

Pointer:

%p base 16 notation, with leading 0x

The %b, %d, %o, %x and %X verbs also work with pointers,

formatting the value exactly as if it were an integer.

The default format for %v is:

bool: %t

int, int8 etc.: %d

uint, uint8 etc.: %d, %#x if printed with %#v

float32, complex64, etc: %g

string: %s

chan: %p

pointer: %p

For compound objects, the elements are printed using these rules,

recursively, laid out like this:

struct: {field0 field1 ...}

array, slice: [elem0 elem1 ...]

maps: map[key1:value1 key2:value2]

pointer to above: &{}, &[], &map[]

Width is specified by an optional decimal number immediately preceding

the verb. If absent, the width is whatever is necessary to represent the

value. Precision is specified after the (optional) width by a period

followed by a decimal number. If no period is present, a default

precision is used. A period with no following number specifies a

precision of zero. Examples:

%f default width, default precision

%9f width 9, default precision

%.2f default width, precision 2

%9.2f width 9, precision 2

%9.f width 9, precision 0

Width and precision are measured in units of Unicode code points, that

is, runes. (This differs from C's printf where the units are always

measured in bytes.) Either or both of the flags may be replaced with the

character '*', causing their values to be obtained from the next operand

(preceding the one to format), which must be of type int.

For most values, width is the minimum number of runes to output, padding

the formatted form with spaces if necessary.

For strings, byte slices and byte arrays, however, precision limits the

length of the input to be formatted (not the size of the output),

truncating if necessary. Normally it is measured in runes, but for these

types when formatted with the %x or %X format it is measured in bytes.

For floating-point values, width sets the minimum width of the field and

precision sets the number of places after the decimal, if appropriate,

except that for %g/%G precision sets the total number of significant

digits. For example, given 12.345 the format %6.3f prints 12.345 while

%.3g prints 12.3. The default precision for %e, %f and %#g is 6; for %g

it is the smallest number of digits necessary to identify the value

uniquely.

For complex numbers, the width and precision apply to the two components

independently and the result is parenthesized, so %f applied to 1.2+3.4i

produces (1.200000+3.400000i).

Other flags:

+ always print a sign for numeric values;

guarantee ASCII-only output for %q (%+q)

- pad with spaces on the right rather than the left (left-justify the field)

# alternate format: add leading 0 for octal (%#o), 0x for hex (%#x);

0X for hex (%#X); suppress 0x for %p (%#p);

for %q, print a raw (backquoted) string if strconv.CanBackquote

returns true;

always print a decimal point for %e, %E, %f, %F, %g and %G;

do not remove trailing zeros for %g and %G;

write e.g. U+0078 'x' if the character is printable for %U (%#U).

' ' (space) leave a space for elided sign in numbers (% d);

put spaces between bytes printing strings or slices in hex (% x, % X)

0 pad with leading zeros rather than spaces;

for numbers, this moves the padding after the sign

Flags are ignored by verbs that do not expect them. For example there is

no alternate decimal format, so %#d and %d behave identically.

For each Printf-like function, there is also a Print function that takes

no format and is equivalent to saying %v for every operand. Another

variant Println inserts blanks between operands and appends a newline.

Regardless of the verb, if an operand is an interface value, the

internal concrete value is used, not the interface itself. Thus:

var i interface{} = 23

fmt.Printf("%v\n", i)

will print 23.

Except when printed using the verbs %T and %p, special formatting

considerations apply for operands that implement certain interfaces. In

order of application:

1. If the operand is a reflect.Value, the operand is replaced by the

concrete value that it holds, and printing continues with the next rule.

2. If an operand implements the Formatter interface, it will be invoked.

Formatter provides fine control of formatting.

3. If the %v verb is used with the # flag (%#v) and the operand

implements the GoStringer interface, that will be invoked.

If the format (which is implicitly %v for Println etc.) is valid for a

string (%s %q %v %x %X), the following two rules apply:

4. If an operand implements the error interface, the Error method will

be invoked to convert the object to a string, which will then be

formatted as required by the verb (if any).

5. If an operand implements method String() string, that method will be

invoked to convert the object to a string, which will then be formatted

as required by the verb (if any).

For compound operands such as slices and structs, the format applies to

the elements of each operand, recursively, not to the operand as a

whole. Thus %q will quote each element of a slice of strings, and %6.2f

will control formatting for each element of a floating-point array.

However, when printing a byte slice with a string-like verb (%s %q %x

%X), it is treated identically to a string, as a single item.

To avoid recursion in cases such as

type X string

func (x X) String() string { return Sprintf("<%s>", x) }

convert the value before recurring:

func (x X) String() string { return Sprintf("<%s>", string(x)) }

Infinite recursion can also be triggered by self-referential data

structures, such as a slice that contains itself as an element, if that

type has a String method. Such pathologies are rare, however, and the

package does not protect against them.

When printing a struct, fmt cannot and therefore does not invoke

formatting methods such as Error or String on unexported fields.

Explicit argument indexes:

In Printf, Sprintf, and Fprintf, the default behavior is for each

formatting verb to format successive arguments passed in the call.

However, the notation [n] immediately before the verb indicates that the

nth one-indexed argument is to be formatted instead. The same notation

before a '*' for a width or precision selects the argument index holding

the value. After processing a bracketed expression [n], subsequent verbs

will use arguments n+1, n+2, etc. unless otherwise directed.

For example,

fmt.Sprintf("%[2]d %[1]d\n", 11, 22)

will yield "22 11", while

fmt.Sprintf("%[3]*.[2]*[1]f", 12.0, 2, 6)

equivalent to

fmt.Sprintf("%6.2f", 12.0)

will yield " 12.00". Because an explicit index affects subsequent verbs,

this notation can be used to print the same values multiple times by

resetting the index for the first argument to be repeated:

fmt.Sprintf("%d %d %#[1]x %#x", 16, 17)

will yield "16 17 0x10 0x11".

Format errors:

If an invalid argument is given for a verb, such as providing a string

to %d, the generated string will contain a description of the problem,

as in these examples:

Wrong type or unknown verb: %!verb(type=value)

Printf("%d", hi): %!d(string=hi)

Too many arguments: %!(EXTRA type=value)

Printf("hi", "guys"): hi%!(EXTRA string=guys)

Too few arguments: %!verb(MISSING)

Printf("hi%d"): hi%!d(MISSING)

Non-int for width or precision: %!(BADWIDTH) or %!(BADPREC)

Printf("%*s", 4.5, "hi"): %!(BADWIDTH)hi

Printf("%.*s", 4.5, "hi"): %!(BADPREC)hi

Invalid or invalid use of argument index: %!(BADINDEX)

Printf("%*[2]d", 7): %!d(BADINDEX)

Printf("%.[2]d", 7): %!d(BADINDEX)

All errors begin with the string "%!" followed sometimes by a single

character (the verb) and end with a parenthesized description.

If an Error or String method triggers a panic when called by a print

routine, the fmt package reformats the error message from the panic,

decorating it with an indication that it came through the fmt package.

For example, if a String method calls panic("bad"), the resulting

formatted message will look like

%!s(PANIC=bad)

The %!s just shows the print verb in use when the failure occurred. If

the panic is caused by a nil receiver to an Error or String method,

however, the output is the undecorated string, "<nil>".

Scanning

An analogous set of functions scans formatted text to yield values.

Scan, Scanf and Scanln read from os.Stdin; Fscan, Fscanf and Fscanln

read from a specified io.Reader; Sscan, Sscanf and Sscanln read from an

argument string.

Scan, Fscan, Sscan treat newlines in the input as spaces.

Scanln, Fscanln and Sscanln stop scanning at a newline and require that

the items be followed by a newline or EOF.

Scanf, Fscanf, and Sscanf parse the arguments according to a format

string, analogous to that of Printf. In the text that follows, 'space'

means any Unicode whitespace character except newline.

In the format string, a verb introduced by the % character consumes and

parses input; these verbs are described in more detail below. A

character other than %, space, or newline in the format consumes exactly

that input character, which must be present. A newline with zero or more

spaces before it in the format string consumes zero or more spaces in

the input followed by a single newline or the end of the input. A space

following a newline in the format string consumes zero or more spaces in

the input. Otherwise, any run of one or more spaces in the format string

consumes as many spaces as possible in the input. Unless the run of

spaces in the format string appears adjacent to a newline, the run must

consume at least one space from the input or find the end of the input.

The handling of spaces and newlines differs from that of C's scanf

family: in C, newlines are treated as any other space, and it is never

an error when a run of spaces in the format string finds no spaces to

consume in the input.

The verbs behave analogously to those of Printf. For example, %x will

scan an integer as a hexadecimal number, and %v will scan the default

representation format for the value. The Printf verbs %p and %T and the

flags # and + are not implemented, and the verbs %e %E %f %F %g and %G

are all equivalent and scan any floating-point or complex value.

Input processed by verbs is implicitly space-delimited: the

implementation of every verb except %c starts by discarding leading

spaces from the remaining input, and the %s verb (and %v reading into a

string) stops consuming input at the first space or newline character.

The familiar base-setting prefixes 0 (octal) and 0x (hexadecimal) are

accepted when scanning integers without a format or with the %v verb.

Width is interpreted in the input text but there is no syntax for

scanning with a precision (no %5.2f, just %5f). If width is provided, it

applies after leading spaces are trimmed and specifies the maximum

number of runes to read to satisfy the verb. For example,

Sscanf(" 1234567 ", "%5s%d", &s, &i)

will set s to "12345" and i to 67 while

Sscanf(" 12 34 567 ", "%5s%d", &s, &i)

will set s to "12" and i to 34.

In all the scanning functions, a carriage return followed immediately by

a newline is treated as a plain newline (\r\n means the same as \n).

In all the scanning functions, if an operand implements method Scan

(that is, it implements the Scanner interface) that method will be used

to scan the text for that operand. Also, if the number of arguments

scanned is less than the number of arguments provided, an error is

returned.

All arguments to be scanned must be either pointers to basic types or

implementations of the Scanner interface.

Like Scanf and Fscanf, Sscanf need not consume its entire input. There

is no way to recover how much of the input string Sscanf used.

Note: Fscan etc. can read one character (rune) past the input they

return, which means that a loop calling a scan routine may skip some of

the input. This is usually a problem only when there is no space between

input values. If the reader provided to Fscan implements ReadRune, that

method will be used to read characters. If the reader also implements

UnreadRune, that method will be used to save the character and

successive calls will not lose data. To attach ReadRune and UnreadRune

methods to a reader without that capability, use bufio.NewReader.

FUNCTIONS

func Errorf(format string, a ...interface{}) error

Errorf formats according to a format specifier and returns the string as

a value that satisfies error.

func Fprint(w io.Writer, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Fprint formats using the default formats for its operands and writes to

w. Spaces are added between operands when neither is a string. It

returns the number of bytes written and any write error encountered.

func Fprintf(w io.Writer, format string, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Fprintf formats according to a format specifier and writes to w. It

returns the number of bytes written and any write error encountered.

func Fprintln(w io.Writer, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Fprintln formats using the default formats for its operands and writes

to w. Spaces are always added between operands and a newline is

appended. It returns the number of bytes written and any write error

encountered.

func Fscan(r io.Reader, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Fscan scans text read from r, storing successive space-separated values

into successive arguments. Newlines count as space. It returns the

number of items successfully scanned. If that is less than the number of

arguments, err will report why.

func Fscanf(r io.Reader, format string, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Fscanf scans text read from r, storing successive space-separated values

into successive arguments as determined by the format. It returns the

number of items successfully parsed. Newlines in the input must match

newlines in the format.

func Fscanln(r io.Reader, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Fscanln is similar to Fscan, but stops scanning at a newline and after

the final item there must be a newline or EOF.

func Print(a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Print formats using the default formats for its operands and writes to

standard output. Spaces are added between operands when neither is a

string. It returns the number of bytes written and any write error

encountered.

func Printf(format string, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Printf formats according to a format specifier and writes to standard

output. It returns the number of bytes written and any write error

encountered.

func Println(a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Println formats using the default formats for its operands and writes to

standard output. Spaces are always added between operands and a newline

is appended. It returns the number of bytes written and any write error

encountered.

func Scan(a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Scan scans text read from standard input, storing successive

space-separated values into successive arguments. Newlines count as

space. It returns the number of items successfully scanned. If that is

less than the number of arguments, err will report why.

func Scanf(format string, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Scanf scans text read from standard input, storing successive

space-separated values into successive arguments as determined by the

format. It returns the number of items successfully scanned. If that is

less than the number of arguments, err will report why. Newlines in the

input must match newlines in the format. The one exception: the verb %c

always scans the next rune in the input, even if it is a space (or tab

etc.) or newline.

func Scanln(a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Scanln is similar to Scan, but stops scanning at a newline and after the

final item there must be a newline or EOF.

func Sprint(a ...interface{}) string

Sprint formats using the default formats for its operands and returns

the resulting string. Spaces are added between operands when neither is

a string.

func Sprintf(format string, a ...interface{}) string

Sprintf formats according to a format specifier and returns the

resulting string.

func Sprintln(a ...interface{}) string

Sprintln formats using the default formats for its operands and returns

the resulting string. Spaces are always added between operands and a

newline is appended.

func Sscan(str string, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Sscan scans the argument string, storing successive space-separated

values into successive arguments. Newlines count as space. It returns

the number of items successfully scanned. If that is less than the

number of arguments, err will report why.

func Sscanf(str string, format string, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Sscanf scans the argument string, storing successive space-separated

values into successive arguments as determined by the format. It returns

the number of items successfully parsed. Newlines in the input must

match newlines in the format.

func Sscanln(str string, a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Sscanln is similar to Sscan, but stops scanning at a newline and after

the final item there must be a newline or EOF.

TYPES

type Formatter interface {

Format(f State, c rune)

}

Formatter is the interface implemented by values with a custom

formatter. The implementation of Format may call Sprint(f) or Fprint(f)

etc. to generate its output.

type GoStringer interface {

GoString() string

}

GoStringer is implemented by any value that has a GoString method, which

defines the Go syntax for that value. The GoString method is used to

print values passed as an operand to a %#v format.

type ScanState interface {

// ReadRune reads the next rune (Unicode code point) from the input.

// If invoked during Scanln, Fscanln, or Sscanln, ReadRune() will

// return EOF after returning the first '\n' or when reading beyond

// the specified width.

ReadRune() (r rune, size int, err error)

// UnreadRune causes the next call to ReadRune to return the same rune.

UnreadRune() error

// SkipSpace skips space in the input. Newlines are treated appropriately

// for the operation being performed; see the package documentation

// for more information.

SkipSpace()

// Token skips space in the input if skipSpace is true, then returns the

// run of Unicode code points c satisfying f(c). If f is nil,

// !unicode.IsSpace(c) is used; that is, the token will hold non-space

// characters. Newlines are treated appropriately for the operation being

// performed; see the package documentation for more information.

// The returned slice points to shared data that may be overwritten

// by the next call to Token, a call to a Scan function using the ScanState

// as input, or when the calling Scan method returns.

Token(skipSpace bool, f func(rune) bool) (token []byte, err error)

// Width returns the value of the width option and whether it has been set.

// The unit is Unicode code points.

Width() (wid int, ok bool)

// Because ReadRune is implemented by the interface, Read should never be

// called by the scanning routines and a valid implementation of

// ScanState may choose always to return an error from Read.

Read(buf []byte) (n int, err error)

}

ScanState represents the scanner state passed to custom scanners.

Scanners may do rune-at-a-time scanning or ask the ScanState to discover

the next space-delimited token.

type Scanner interface {

Scan(state ScanState, verb rune) error

}

Scanner is implemented by any value that has a Scan method, which scans

the input for the representation of a value and stores the result in the

receiver, which must be a pointer to be useful. The Scan method is

called for any argument to Scan, Scanf, or Scanln that implements it.

type State interface {

// Write is the function to call to emit formatted output to be printed.

Write(b []byte) (n int, err error)

// Width returns the value of the width option and whether it has been set.

Width() (wid int, ok bool)

// Precision returns the value of the precision option and whether it has been set.

Precision() (prec int, ok bool)

// Flag reports whether the flag c, a character, has been set.

Flag(c int) bool

}

State represents the printer state passed to custom formatters. It

provides access to the io.Writer interface plus information about the

flags and options for the operand's format specifier.

type Stringer interface {

String() string

}

Stringer is implemented by any value that has a String method, which

defines the ``native'' format for that value. The String method is used

to print values passed as an operand to any format that accepts a string

or to an unformatted printer such as Print.

- 查看某个包中某个函数

C:\Users\zhang>godoc fmt Println

use 'godoc cmd/fmt' for documentation on the fmt command

func Println(a ...interface{}) (n int, err error)

Println formats using the default formats for its operands and writes to

standard output. Spaces are always added between operands and a newline

is appended. It returns the number of bytes written and any write error

encountered.

七.gofmt工具

1.gofmt工具介绍

- 规范的代码方便自己的阅读也方便别人的阅读.编写规范代码是每个程序的必修课

- gofmt工具可以帮助程序员把代码进行格式化,按照规范进行格式化

- 使用gofmt前提是文件编译通过

2. 不规范代码示例

- 查看下面代码中不规范的地方有几处

package main

import "fmt"

func main ( ){

fmt.Println("hello word");

}

3.使用gofmt的步骤

gofmt 文件名D:\go\0201>gofmt main.go

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("hello word")

}

- 通过运行gofmt后发现规范的代码和不规范代码的几处区别

- package关键字和import关键字和func main之间有空行

- main和括号之间没有空格

- main后面()之间没有空格

- ()和{之间有空格

- fmt.Println()前面有缩进

- fmt.Println()后面没有分号